Scientists have deciphered a key strategy of cancer cells that allows them to outfox the immune system and enhance the odds of their survival by employing a deadly “two-faced protein” that is reminiscent of a two-faced figure in ancient Roman mythology.

Cancers are genetically programmed to survive at all costs, even if that quest means killing its host as is too often the case when a malignancy becomes metastatic. Prime among a tumor’s tools is a cytokine by the name of TGF-β1—or just TGF-β for short—a molecule that immunobiologists in Switzerland have dubbed a “two-faced protein.” The name is derived from the complex biological role that TGF-β plays—it can both suppress and promote the growth of human tumors. One of its key roles is to suppress the cancer-killing activities of T cells.

In many ways, TGF-β is much like the ancient Roman god Janus, who also had two faces symbolizing the stark differences he played in mythology. One face of Janus looked to the future; the other had a sharp eye on the past.

Dr. Sarah Dimeloe, an immunobiologist at the University of Basel, and a team of investigators, have shed new light on the cell-specific effects of TGF-β, discoveries that may pave the way for new therapies that zero in on the deleterious properties of the protein without erasing its benefits.

“Many tumor types produce TGF-β in large quantities, and this is associated with metastasis and poor patient prognosis,” Dimeloe indicated, underscoring that “tumor-promoting activities of TGF-β include dysregulation of the cell cycle, increased extracellular matrix formation, angiogenesis, and, most importantly, inhibition of antitumor T cell immunity.”

As extensive as those activities may seem, the complexity of TGF-β is deeper still, Dimeloe and her colleagues have found. And while it may be difficult to imagine a protein with two dramatically different “faces,” it may be even more difficult to contemplate cancer cells exhibiting traits, such as cunning and deception. But the research underway at the University of Basel, and collaborating laboratories, has revealed that TGF-β not only is a two-faced protein, it also is one that seems almost Machiavellian in its activities.

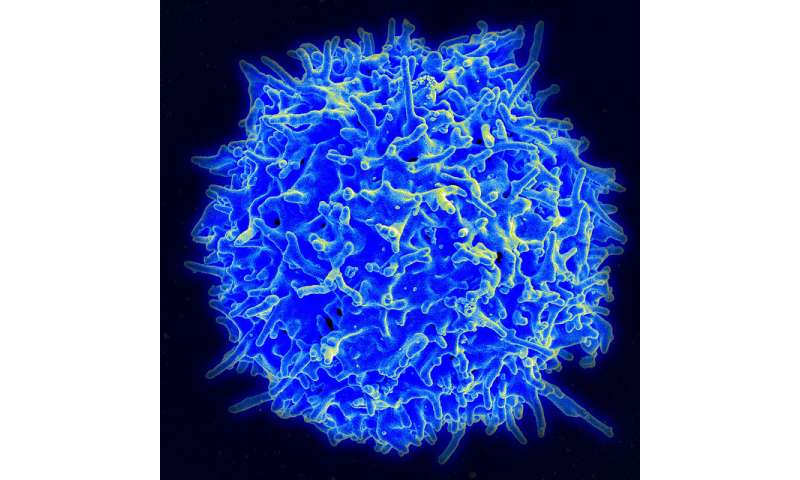

The protein not only inhibits T cell antitumor activity, but other antitumor capabilities mounted by the immune system as well, allowing TGF-β to impair singlehandedly facets of the body’s antitumor armamentarium. Dimeloe and her colleagues have found that TGF-β accomplishes this suppression by initiating potent signaling activity that subverts T cell efforts to keep cancer at bay.

Among TGF-β’s prime tumor-driving roles is initiating the process of angiogenesis, the sprouting of blood vessels. New vasculature allows a tumor to tap into its host’s blood supply from which the cancer gathers nutrients to support its growth and proliferation.

Yet as devastating as TGF-β can be in the progression of cancer, the protein has a completely different “face” in healthy tissue, just as one face of Janus was a dramatic opposite of the other.

TGF-β1 stands for transforming growth factor beta-1, a polypeptide and member of a vast superfamily of cytokines. It is a secreted protein with a host of beneficial biological roles. These include cell differentiation and proliferation, as well as initiating apoptosis, or programmed cell death. TGF-β plays these beneficial roles throughout the body and is present in virtually all tissues. It is especially abundant in the kidneys, lungs, bones and placenta.

Nevertheless, Dimeloe and her team, who reported their research in the journal Science Signaling, found that massive amounts of TGF-β are secreted by tumors not only to promote the formation of tumor blood vessels, but also to alter the growth cycle of cells.

At the heart of their investigation, Dimeloe and her investigators analyzed fluid samples secreted by various human metastatic tumors. They also tracked how these fluids, which are all abundant in TGF-β, affected CD4+ T cells. They discovered that tumor-secreted TGF-β impaired the metabolism and mitochondrial activity of CD4+ T cells. TGF-β additionally blocked the production of interferon-gamma, a key antitumor molecule.

Dimeloe and her team traced that deleterious effect to an increase in the phosphorylation of SMAD proteins within the mitochondria of CD4+ T cells. SMADs are a subfamily of intracellular proteins that deliver extracellular signals from TGF-β, leading to the activation of downstream gene transcription that regulates cell growth and division.

That impact on the mitochondria proves devastating across a range of cancers because “TGF-β substantially impaired the ATP-coupled respiration of CD4+ T cells and specifically inhibited mitochondrial complex 5,” Dimeloe and her team wrote in their research paper, referring to the enzyme ATP synthase.

ATP synthase, which looks something like a turbine and functions like a machine, produces energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate, ATP, the main cellular energy source. Without ATP, CD4+ T cells are a powerless army.

“These results, which have implications for human anti-tumor immunity, suggest that TGF-β targets T cell metabolism directly, thus diminishing T cell function through metabolic paralysis,” the team concluded.

Dimeloe and her colleagues also found that detrimental effects caused by the “bad” face of TGF-β are consistent across a diverse range of cancers. As a result of their findings, the investigators are proposing the development of a small molecule that selectively zeroes in on tumor-generated TGF-β and its impact on CD4+ T cells.

Source: Read Full Article