During the coronavirus pandemic, the mental health of adolescents suffered to an extraordinary degree. To what extent school closures contributed to or even caused this crisis was so far largely unknown.

In collaboration with the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Christina Felfe, Professor of Applied Microeconomics at the University of Konstanz, and her team (Judith Saurer, Patrick Schneider and Judith Vornberger) are now able to show that school closures during the first wave of the pandemic led to a significant deterioration in the mental health of adolescents.

Effects were most severe among male adolescents, younger adolescents and families with limited living space. Their findings have been published in the latest issue of the journal Science Advances.

“Our objective was to analyze what impact school closures had during this very vulnerable period in people’s lives, in which social bonds, contacts with role models, with teachers, but also with classmates are a deciding factor for healthy development,” says Christina Felfe.

As an economist, she is interested in the cost-benefit analysis of the measures, whereby costs are understood to mean the damage caused by the Coronavirus Protection Ordinance. How much did school closures contribute to containing the pandemic, and what are the costs in this sense?

Germany as a ‘natural laboratory’

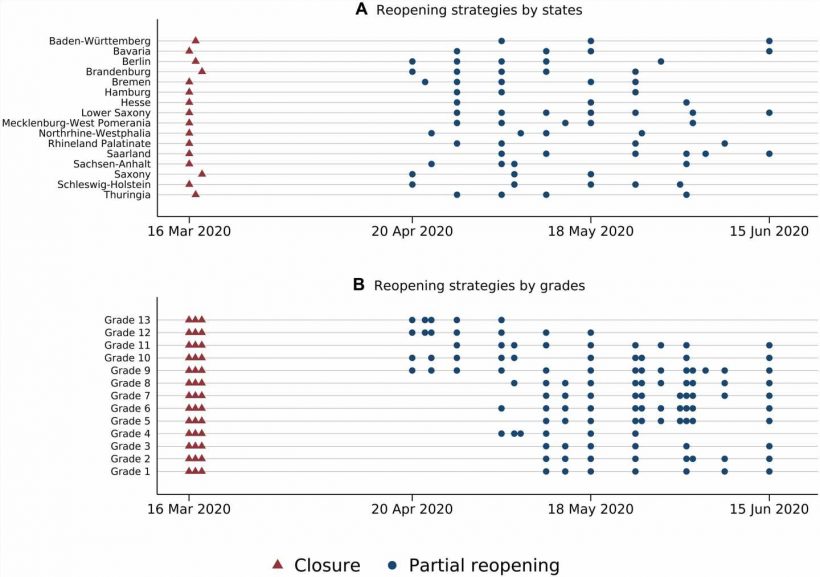

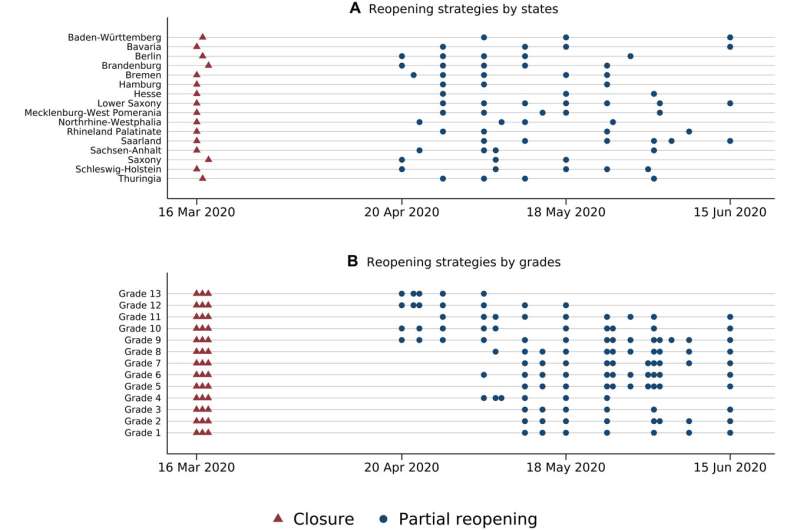

She and her research associates Judith Vornberger, Patrick Schneider and Judith Saurer based their study on the dataset of Judith Vornberger summarizing the federal political structure in Germany. Since the 16 German states enjoy educational sovereignty, they were able to decide independently on school closure and reopening strategies. This “natural laboratory” enabled the researchers to explore the impact of school closures of different lengths on adolescents’ mental health.

For this purpose, Judith Vornberger screened all state-specific coronavirus protection ordinances, in this way creating a dataset of state-specific school closure and reopening strategies, which they evaluated together with data from the COPSY study (COVID-19 and PSYchological health survey) conducted by the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf.

In the COPSY study, participants were asked about depression levels, psychosomatic complaints, socio-emotional and behavioral difficulties, independently of any clinically diagnosed illnesses.

“Each state followed its own strategy. We based our study on the fact that not all adolescents were at home for the same length of time,” says Christina Felfe. Depending on the grade adolescents were in and in which state they resided, they were at home for shorter or longer periods of time. By isolating state-specific characteristics, it was possible to make a nationwide comparison.

It emerged that 11- to 17-year-old adolescents were, on average, as bad off during the first wave of the pandemic as the 15 percent of adolescents whose mental well-being was poorest prior to it. Those aged between 11 and 14 years were hit particularly hard and coped worse than 15- to 17-year-olds. The ability to shoulder the burden imposed by school closures varied depending on age, gender and living conditions.

Families were left alone

The researchers discovered that 11- to 17-year-old adolescents on average fared far worse than others during the first wave of the pandemic. This deterioration in well-being is a direct consequence of school closures. Adolescents between 11 and 14 years of age were hit particularly hard and coped less well with the new situation than fifteen- to seventeen-year-olds.

Boys coped worse with school closures than girls. Adolescents in households with limited living space suffered most from the strain of school closures. “The nationwide deterioration can be explained entirely by school closures. Families were largely left to deal with the unparalleled situation at home, including the multiple stresses of juggling work, school and family life,” underlines Christina Felfe.

“We must ensure now that we bolster our schools and support them in making children and adolescents more resilient to future crises. For this we need low-threshold, sustainable and long-term concepts and structures in order to reach children and adolescents with psychological problems and offer them help,” says Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, head of the study and of the “Child Public Health” research group in the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE).

The datasets

The COPSY study used an online questionnaire to ask children and adolescents in Germany about the effects and consequences of the pandemic on their mental health and well-being. This survey built on the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents, which has been conducted by the Robert Koch Institute for 20 years.

The BELLA study (survey on mental well-being and behavior), also led by Ulrike Ravens-Sieberer, was likewise included, as were data from Germany’s largest crisis helpline “Nummer gegen Kummer.” These data were merged with the dataset on the various school closures in the 16 German states compiled by Judith Vornberger.

In further projects, Christina Felfe and her team want to examine to what extent children under 11 years of age and their parents suffered as a result of school closures.

More information:

Christina Felfe et al, The youth mental health crisis: Quasi-experimental evidence on the role of school closures, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adh4030

Journal information:

Science Advances

Source: Read Full Article