During a single overnight shift this week, three new COVID-19 patients were rushed into Dr. Karim Debbat’s small intensive care ward in the southern French city of Arles. It now has more virus patients than during the pandemic’s first wave and is scrambling to create new ICU beds elsewhere in the hospital to accommodate the sick.

Similar scenes are playing out across France.

COVID-19 patients now occupy 40% of ICU beds in the Paris region, and more than a quarter of ICUs nationwide as weeks of growing infections among young people spread to vulnerable populations.

Despite being one of the world’s richest nations—and one of those hardest hit when the pandemic first washed over the world—France hasn’t added significant ICU capacity or the staff needed to manage extra beds, according to national health agency figures and doctors at multiple hospitals.

Like in many countries facing resurgent infections, critics say France’s leaders haven’t learned their lessons from the first wave.

“It’s very tense, we don’t have any more places,” Debbat told The Associated Press. The Joseph Imbert Hospital in Arles is converting recovery rooms into ICUs, delaying non-urgent surgeries and directing more and more of his staff to high-maintenance COVID-19 patients.

Asked about extra medics to help with the new cases, he said simply, “We don’t have them. That’s the problem.”

When protesting Paris public hospital workers confronted French President Emmanuel Macron this week to demand more government investment, he said: “It’s no longer a question of resources, it’s a question of organization.”

He defended his government’s handling of the crisis, and noted 8.5 billion euros ($9.3 million) in investment promised in July for the hospital system. The protesting medics said the funds are too little and too slow in coming, after years of cuts that left France with half the number of ICU beds in 2020 that it had in 2010.

ICU occupancy rates are considered an important indicator of how saturated the hospital system is and how effective health authorities have been at protecting at-risk populations. And France’s numbers aren’t looking good.

It reported a record daily count of more than 20,300 new virus cases Friday, and COVID patients now occupy 1,439 ICU beds nationwide—a figure that has doubled in less than a month. France’s overall ICU capacity is 6,000, roughly the same as in March, according to national health agency figures provided to the AP.

In comparison, Germany entered the pandemic with about five times as many intensive care beds as France. To date, Germany’s confirmed virus-related death toll is 9,584 compared to 32,521 people in France.

Getting ICU capacity right is a challenge. Spain was caught short in the spring, and has ihigh-speed train from hotspots to less saturated areas. The health agency said French hospitals could eventually double their ICU capacity if needed this fall.

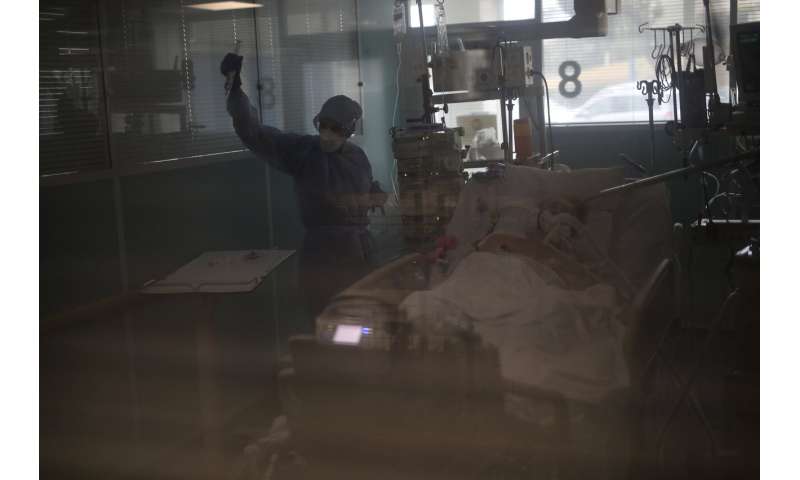

Compared to March and April, doctors say French intensive care wards are better armed this time around, both with protective equipment and more knowledge about how this coronavirus works. Medics put fewer patients on breathing machines now and hospitals are practiced in how to rearrange their operations to focus on COVID-19.

The number of virus patients in the ICU quickly doubled last month in the New Civilian Hospital in Strasbourg, but the atmosphere is surprisingly calm. An AP reporter watched teams of medics coordinating closely to manage the trajectory and treatment of each patient according to strict protocols they’re now accustomed to.

But that extra practice doesn’t mean managing resurgent virus cases in ICUs is easy. In addition to extra breathing machines and other equipment, adding temporary ICU beds also takes time and labor – as does treating the COVID-19 patients in them.

“The work is harder, and takes longer” than for most other patients, said Pierre-Yves, head of the intensive care ward at the Laveran Military Training Hospital in Marseille. He was not authorized to be identified by his last name because of military policy.

Seven or more of his 47 staffers are needed each time they slowly and carefully rotate a patient from back to stomach or vice versa. Entering and leaving the ward now involves a lengthy, careful dance of changing full-body gear and disinfecting everything they’ve touched.

Dr. Debbat in Arles said training ICU staff takes several months, so he’s relying on the same personnel levels as in the spring, and he worries they could burn out.

“I’m like a coach and I have just one team, with no reserve players,” he said.

He also worries about non-virus patients, who were already put on the back burner earlier this year. And he worries about the upcoming flu season, which sends about 2,000 patients to ICUs in France every year.

The head of emergency medical service SOS Medecins, Serge Smadja, doesn’t think France will again face the situation it saw in the spring, when more than 7,000 virus patients were in intensive care at the peak of the crisis, and some 10,000 infected people died in nursing homes without ever making it to hospitals. But he said the French public and its leaders were wrong to think “the virus was behind us.”

Source: Read Full Article