Routine testing for bowel cancer should not be recommended for everyone aged 50-79 years because, for those at very low risk, the benefit is small and uncertain and there are potential harms, say a panel of international experts in The BMJ today.

But they say screening should be recommended for men and women with a risk of 3% or more in the next 15 years, as this is the point at which the balance of benefits and harms tilts in favour of screening.

Their advice is based on the latest evidence and is part of The BMJ‘s ‘Rapid Recommendations’ initiative—to produce rapid and trustworthy guidance based on new evidence to help doctors make better decisions with their patients.

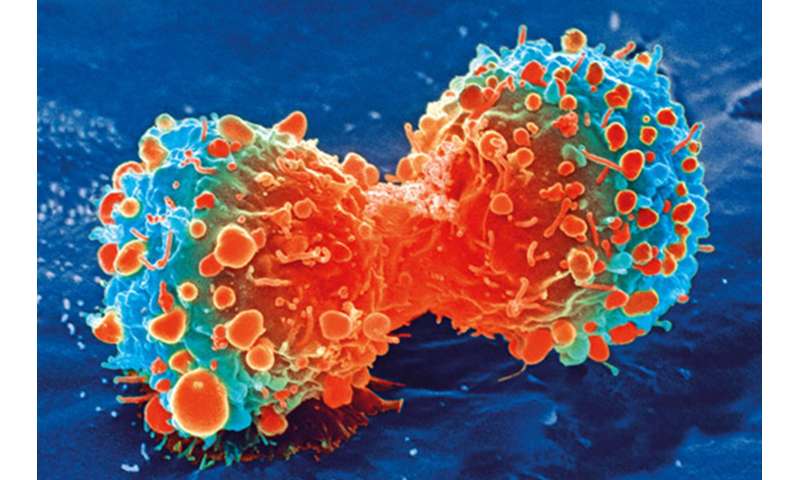

Bowel (colorectal) cancer is a common type of cancer in men and women—about 1 in 20 people in most high income countries will get it during their lifetime. A person’s risk depends on their age, sex, genetics and lifestyle factors, such as alcohol intake, smoking, physical activity and diet.

Most guidelines recommend screening for everyone from age 50, irrespective of their individual risk. At this age, the risk of developing bowel cancer over the next 15 years is typically 1-2%, meaning that in a group of 100 people with the same risk factors, one or two will develop bowel cancer within the next 15 years.

The four most common screening options are home faecal testing (FIT) every year or every two years, sigmoidoscopy (examination of the lower colon) or colonoscopy (examination of the entire colon) done at a clinic or hospital.

Recently published research on the long term effects of bowel cancer screening has shed new light on the benefits and harms, and has the potential to change current recommendations.

So an international panel made up of researchers, clinicians and patients, reviewed the evidence base, including this new evidence, to evaluate the benefit-to-harm balance of screening using a “risk based approach.”

This means they took account of an individual’s cumulative risk of bowel cancer over the next 15 years together with risk of harm from the procedure (e.g. bowel perforations, unnecessary treatment) and quality of life (e.g. anxiety, burden of procedure), as well as a person’s values, preferences, and life expectancy.

Their recommendations apply to healthy individuals aged 50-79 years with a life expectancy of at least 15 years.

For men and women with an estimated 15-year bowel cancer risk below 3%, they suggest no screening, and say most informed individuals in this group are likely to decline screening.

However, for men and women with an estimated 15-year bowel cancer risk above 3%, they suggest screening with one of the four options, and say most informed individuals in this group are likely to choose screening after discussing the potential benefits and harms with their doctor.

The panel does not recommend any one test over another, but they found convincing evidence that people’s values and preferences on whether to test and what test to have varies considerably.

For example, some people will want to avoid an invasive test like colonoscopy, and may prefer faecal testing. While those who most value preventing bowel cancer or avoiding repeated testing are likely to choose sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

The authors stress that there are still many uncertainties in terms of what is the most effective screening test or combination of tests, and at what age and interval they should be used, and suggest this should be the focus of future research. These recommendations may also be altered as new evidence emerges, they conclude.

The evidence backing colorectal cancer screening “is still fragile and strong recommendations cannot be issued at the moment,” writes Professor Philippe Autier at the International Prevention Research Institute (iPRI) in a linked editorial.

He welcomes the shift away from maximizing uptake of screening to a personalised approach based on individual risk and informed choice, which he says has several advantages over offering screening to everyone in eligible age groups.

Source: Read Full Article