The microbiome has a tremendous influence on the health and disease susceptibility of humans. Although genetics plays some part in determining the diversity of the microbiome, diet has the largest influence; therefore, humans can make certain lifestyle choices that have been proven to increase the diversity and stability of their microbiome.

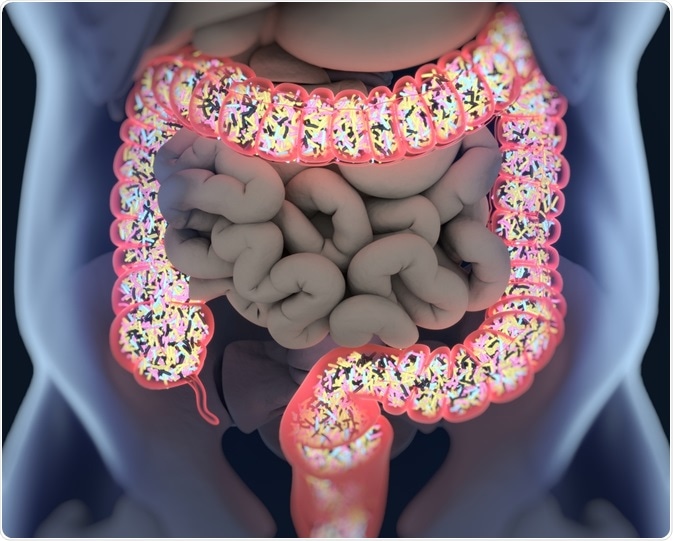

Image Credit: Anatomy Insider/Shutterstock.com

What is the microbiome?

It is estimated that at least 100 trillion (1014) microbial cells and millions of viruses reside within the human body, all of which produce various enzymes, chemicals, hormones, and vitamins that can interact with other human cells.

This complex community of microorganisms, which is more commonly referred to as the microbiota, can be of viral, bacteria, archaea, and/or eukaryotic etiologies. Comparatively, the genes that these organisms encode for is known as the microbiome.

As a result of extensive research that has been conducted over the past few decades, the microbial organisms can have significant impacts on the health of humans.

Moreover, the microbiome can determine how the immune system responds to potential pathogens, the rate at which nutrients and energy are absorbed from the diet as well as certain psychological and behavioral states.

When the balance between the gut microbiota and the host is disrupted, which is a condition otherwise referred to as dysbiosis, various health conditions can occur, some of which include malnutrition, inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), obesity, neurological disorders, and cancer.

Early diversification of the microbiome

During fetal development and infancy, the diversity of both the bacteria and viruses that comprise the microbiome is generally low. Since the gut, during these early stages of life, contains oxygen, the microorganisms that are present within the gut at this time are mostly aerotolerant.

As the child develops, these organisms are replaced by anaerobes. This evolution of microbial organisms within the gut is rapid, as studies have even shown that 56% of the virome sequences found within the gut of infants during their first week of life are not present after the second week.

This diversity continues to expand rapidly throughout the first 3 months of life, which is comparable to the virome of the adult microbiome, in which approximately 95% of these microorganisms are conserved over time.

Since virus particles are not present in either formula or breast milk, researchers believe that this early diversification of the microbiome is the result of environmental exposures and maternal contact.

What determines microbiome diversity?

Genetics

The two primary determinants of an individual’s microbiome diversity include genetics and the environment, which includes antibiotic treatment, cesarean births, and diet. Individuals who are related, for example, have more similar microbiota compositions as compared to when two unrelated people are studied.

However, studies have shown that both monozygotic and dizygotic adult twins share equally similar microbiota, thereby demonstrating that the environment plays a much larger role in determining the diversity of an individual’s microbiome as compared to genetics.

In fact, it has been estimated that a 60% variation in the diversity of the microbiome is environmentally determined and that 0.30 to 0.37 of the gut microbiome diversity is heritable.

Geography and culture

One study comparing both children and adults in Malawi, Venezuela and the United States found that, aside from genetics, these populations differ considerably in their environmental exposures, hygiene, diet, and antibiotic use, which, taken together, have important effects on their microbiota.

Children in a rural African village of Burkina Faso, who typically consume a high-fiber diet, were found to have higher levels of the Prevotella bacterial species within their gut microbiome. Similar levels of Prevotella were found in the gut microbiome of both children and adults in Malawi and Venezuela, both of whom typically consume diets that are high in corn, cassava, and other plant-based polysaccharides.

Comparatively, individuals in the United States were found to have higher levels of Bacteroides in their microbiome, which is associated with a long-term diet that is rich in animal protein, several amino acids, and saturated fats.

In addition to reflecting on differences in cultural diets, these distinctions between the microbiota of individuals from certain countries also have an underlying role in determining the disease vulnerability of these individuals.

For example, the incidence of IBD and general allergies is substantially higher in Western societies as compared to individuals residing in traditional agrarian cultures.

A high fiber diet

Upon consumption of food, bacteria within the gut ferment dietary fiber and generate short-chain fatty acids, which has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and fatty acid oxidation.

By definition, dietary fiber includes edible carbohydrate polymers that are comprised of three or more monomeric units. Taken together, these monomers are resistant to the endogenous enzymes that inhabit the gastrointestinal tract, thereby preventing their absorption in the small intestine.

Dietary fibers can be found in various fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, legumes, and cereals.

When presented with dietary fiber, the various microbial organisms that make up the microbiome can utilize these substrates to expand their populations, thereby increasing the overall diversity of the microbiome.

In fact, many of the anaerobic bacteria that reside within the colon and cecum are reliant upon the metabolism of complex carbohydrates to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which play key roles in host metabolism, immune function, and cell proliferation.

Additionally, a high fiber diet, which subsequently assists in the development of a highly diverse microbiome, has also been shown to reduce the risk of weight gain in several studies.

To this end, the consumption of a high fiber diet reduces the energy density of the diet, thereby causing SCFAs in the body to promote a greater level of gluconeogenesis to occur in the body. This causes incretin to form, which causes individuals to feel full quicker and for longer periods.

Image Credit: Colorcocktail/Shutterstock.com

The harm of highly processed diets

Many of the components that make up the Western diet contribute to the reduced diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiota. Not only is this type of diet low in dietary fiber, but it is also associated with high sugar, fat, and meat protein intake.

Whereas high sugar consumption can lead to hyperglycemia and high fat consumption can cause the level of toxic bile acids to rise, a diet that is low in fiber and high in animal protein can also contribute to the production of toxic metabolites in the body.

Taken together, each of these effects can enhance the degradation of mucus within the gastrointestinal tract and reduce the production of antimicrobial peptides. As mucus levels diminish, the penetrability of the intestinal layers rises, thereby increasing the susceptibility of these individuals to infections.

Rather than utilize normal gut microbial metabolic pathways, this type of diet instead relies on the metabolism of other substrates, such as proteins, thereby contributing to detrimental health effects since these nutrients are needed for other bodily functions.

Conclusion

Research has found that even when the daily recommended fiber intake of approximately 30 grams per day is ingested, dietary fiber levels are too low to achieve a symbiosis between individuals and their microbiota.

Although increasing fiber intake is generally associated with a more diverse microbiome, it should be noted that certain undesirable side effects may occur for individuals who cannot tolerate these high doses of fiber, such as those with IBD.

In light of this information, it is recommended that specific fiber types are consumed based on an individual’s specific microbiota profile.

Not only will this reduce the occurrence and severity of unwanted side effects, but it is expected that the host will experience the physiologic benefit associated with increasing their fiber intake.

References and Further Reading

- Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., et al. (2012). Diversity, stability, and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489(7415); 220-230. doi:10.1038/nature11550.

- Clemente, J. C., Ursell, L. K., Parfrey, L. W., & Knight, R. (2012). The Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Human Health: An Integrative View. Cell 148(6); 1258-1270. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035.

- Menni, C., Jackson, M. A., Pallister, T., Steves, C. J., et al. (2017). Gut microbiome diversity and high-fibre intake are related to lower long-term weight gain. International Journal of Obesity 41; 1099-1105. doi:10.1038/ijo.2017.66.

- Makki, K., Deehan, E. C., Walter, J., & Backhed, F. (2018). The Impact of Dietary Fiber on Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease. Cell Host & Microbe 23; 705-715. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012.

Further Reading

- All Microbiome Content

- The Human Microbiome Project (HMP)

- How Does the Diet Impact Microbiota?

- Achievements of the Human Microbiome Project

- Human Microbiome

Last Updated: Jul 31, 2020

Written by

Benedette Cuffari

After completing her Bachelor of Science in Toxicology with two minors in Spanish and Chemistry in 2016, Benedette continued her studies to complete her Master of Science in Toxicology in May of 2018.During graduate school, Benedette investigated the dermatotoxicity of mechlorethamine and bendamustine, which are two nitrogen mustard alkylating agents that are currently used in anticancer therapy.

Source: Read Full Article