The building blocks of a structure consist of load-bearing elements that rarely change despite renovations or repairs. They remain intact and consistent over time, but in the human body, our building blocks do just the opposite.

Bones are dynamic: They constantly break down and rebuild to become the strongest versions of themselves.

A mutation in this bone regeneration process can lead to weak and fragile bones, and if the mutation is related to the generated amount of collagen—a protein found in bone, connective tissue, skin and cartilage—it leads to brittle bone disease.

Brittle bone disease, also known as osteogenesis imperfecta, currently affects 20,000–50,000 people in the United States but is also the most commonly inherited bone disease. It often begins in utero, and in many cases, physicians can see fractures in the baby’s limbs before they are even born. And these patients are likely to go on to break multiple bones during their lifetime. Meenal Mehrotra, M.D., Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the department of surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina, and she says that there is currently no cure for the disease. She also points out that physicians mainly focus on treating the symptoms of brittle bones, but that that can have its own uncomfortable side effects.

Her goal is to find a safer method to treat this devastating disease.

Healthy bone constantly experiences and remodels its own microfractures, according to Mehrotra. “Bone-resorbing cells known as osteoclasts chew away at the affected area,” she said. “And then osteoblasts, which are bone-forming cells, come and rebuild that portion of the bone.”

There are medications called bisphosphonates that are currently being used to treat brittle bone disease which influence osteoclast levels. By reducing osteoclasts and thus bone breakdown, there is more bone formed. But Mehrotra says this doesn’t fix the root problem, as the bone formed is also defective in nature.

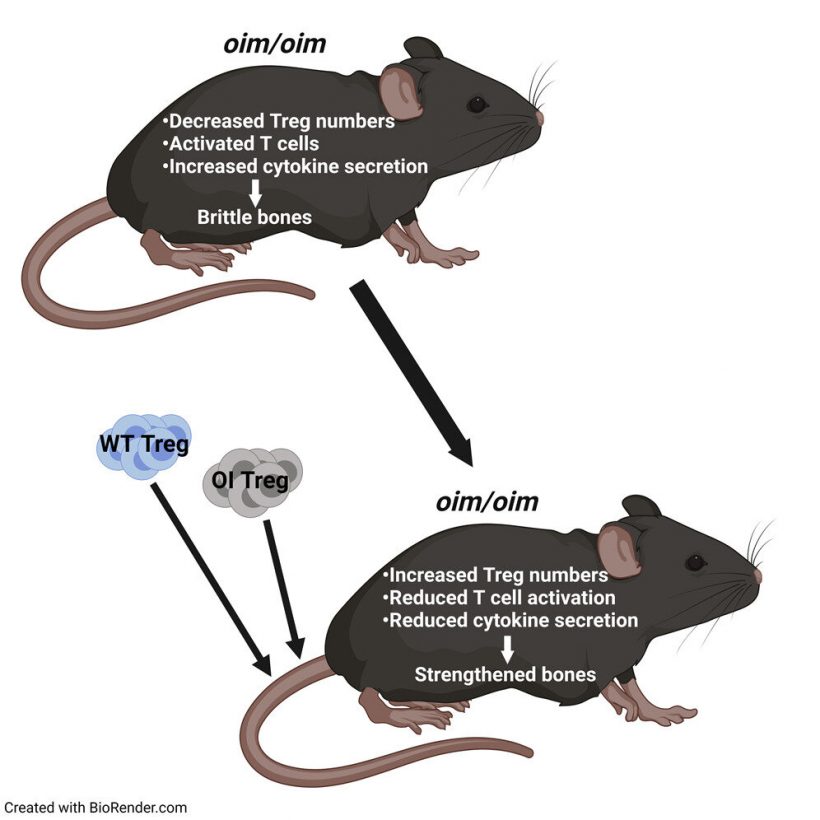

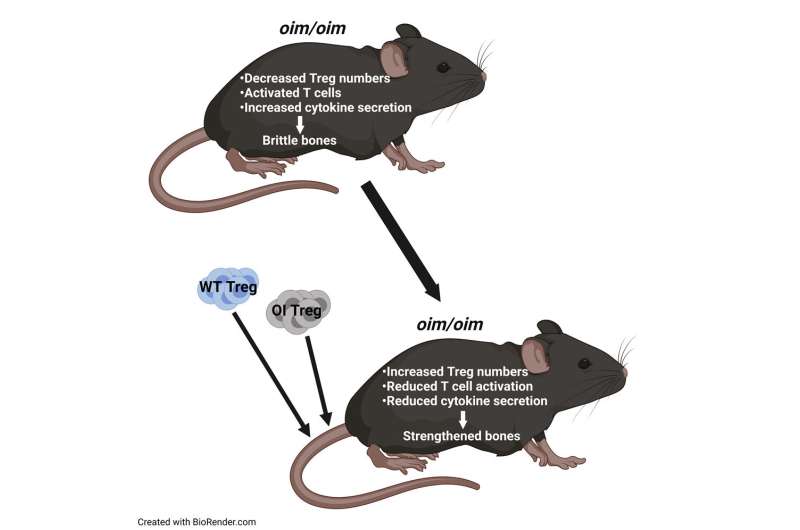

In a recent paper in iScience, the team looks at regulatory T cells, or Treg cells, as a previously uninvestigated treatment for brittle bone disease. Treg cells help maintain balance and homeostasis in the body by keeping the activity of the immune cells (T cells) in check. When activated, T cells release cytokines, which in turn lead to inflammation. But when enough Treg cells are present, T cells aren’t as highly activated, which means there are fewer cytokines and less inflammation.

They found that the internal environment of mice with this disease is hyperinflamed due to fewer Tregs. Mehrotra hypothesized that increasing these Treg numbers in mice with brittle bone disease could lead to untapped treatment options.

Through Treg transplantations, researchers proved that increasing the number of Tregs does indeed enhance bone remodeling which in turn led to stronger bones.

Mehrotra and her team tested Treg cell transplantation with both the affected mouse’s own T cells (autotransplantation) and a donor mouse’s T cells (allotransplantation) and compared the results. While both methods resulted in higher levels of Treg cells and stronger bones, she found that by extracting the subject’s own Treg cells and increasing those levels before transplanting them back, treatment results may actually last longer.

With both transplantations, Mehrotra saw increased osteoblast numbers and decreased osteoclast numbers. There was more of a balance. “It’s very exciting,” she said. “We saw better bone architecture and better bone mechanics. Bones were stiffer.”

But the most exciting part to her is that while allotransplantation and autotransplantation both worked, the results with autotransplantation were better than those seen with allotransplantation. Projecting toward a potential clinical perspective, using a patient’s own cells would allow for less donor rejection and no use of immunosuppressants. “It would be easier on our patients,” she said.

After studying hematopoietic stem cells and brittle bone disease in a previous study, Mehrotra had the idea to look at Treg cells. And when she started researching the topic, she realized no one had yet looked at Treg cell transplantation as an immunotherapy treatment option for patients with this disease. She is looking forward to continuing this promising line of research in the future.

She next wants to look at why a genetic disease of collagen mutation that seemingly has no relationship to immunity carries an immunological deficit.

Moreover, she wants to look at how increasing the Tregs specifically brings about the positive changes in the bone. “That’s the other part of the puzzle for me,” she said.

Source: Read Full Article