Editor’s Note: This is the first in a two-part series commemorating the 100 year anniversary of the first use of insulin in humans. The second part focuses on how insulin and the treatment of type 1 diabetes have changed over the past 100 years and what to expect in the next 100.

Leonard Thompson’s father was so desperate to save his 14-year-old child from certain death due to diabetes that, on January 11, 1922, he took him to Toronto General Hospital to receive what is arguably the first dose of insulin given to a human. From an anticipated life expectancy of weeks — months at best — Thompson lived for an astonishing further 13 years, eventually dying from pneumonia unrelated to diabetes.

By all accounts, the story is a centenary celebration of a remarkable discovery. Insulin has changed what was once a death sentence to a near-normal life expectancy for the millions of people with type 1 diabetes over the past 100 years.

But behind the life-changing success of the discovery — and the Nobel Prize that went with it — lies a tale blighted by disputed claims, twisted truths, and likely injustices between the scientists involved, as they each vied for an honored place in medical history.

Kersten Hall, PhD, honorary fellow, religion and history of science, at the University of Leeds, UK, has scoured archives and personal records held at the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, to uncover the personal stories behind insulin’s discovery.

Despite the wranglings, Hall asserts: “There’s a distinction between the science and the scientists. Scientists are wonderfully flawed and complex human beings with all their glorious virtues and vices, as we all are. It’s no surprise that they get greedy, jealous, and insecure.”

At Death‘s Door: Diabetes Before the 1920s

Dr Charles Best

Prior to insulin’s discovery in 1921, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes placed someone at death’s door, with nothing but starvation — albeit a slightly slower death — to mitigate a fast-approaching departure from this world. At that time, most diabetes cases would have been type 1 diabetes because, with less obesogenic diets and shorter lifespans, people were much less likely to develop type 2 diabetes.

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is on a steep upward curve, but so too is type 1 diabetes. In the US alone, there are 1.5 million people diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a number expected to rise to around 5 million by 2050, according to JDRF, the type 1 diabetes advocacy organization.

Interestingly, 100 years since the first treated patient, life-long insulin remains the only real effective therapy for patients with type 1 diabetes. Once pancreatic beta cells have ceased to function and insulin production has stopped, insulin replacement is the only way to keep blood glucose levels within the recommended range (A1c ≤ 48 mmol/mol [6.5%]), according to the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), as well as numerous diabetes organizations, including the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

Preliminary clinical trials have looked at stem cell transplantation, prematurely dubbed as a “cure” for type 1 diabetes, as an alternative to insulin therapy. The procedure involves transplanting stem cell–derived cells, which become functional beta cells when infused into humans, but requires immunosuppression, as reported by Medscape.

Today, the life expectancy of people with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin is close to those without the disease, although this is dependent on how tightly blood glucose is controlled. Some studies show life expectancy of those with type 1 diabetes is around 8 to 12 years lower than the general population but varies depending on where a person lives.

In some lower-income countries, many with type 1 diabetes still die prematurely either because they are undiagnosed or cannot access insulin. The high cost of insulin in the US is well publicized, as featured in numerous articles on Medscape, and numerous patients in the United States have died because they cannot afford insulin.

Without insulin, young Leonard Thompson would have been lucky to have reached his 15th birthday.

“Such patients were cachectic and thin and would have weighed around 40-50 pounds (18-23 kg), which is very low for an older child. Survival was short and lasted weeks or months usually,” remarks Elizabeth Stephens, MD, an endocrinologist in Portland, Oregon.

“The discovery of insulin was really a miracle because without it diabetes patients were facing certain death. Even nowadays, if people don’t get their insulin because they can’t afford it or for whatever reason, they can still die,” Stephens stresses.

Antidiabetic Effects of Pancreatic Extract Limited

Back in 1869, Paul Langerhans, MD, discovered pancreatic islet cells, or islets of Langerhans, as a medical student. Researchers tried to produce extracts that lowered blood glucose but they were too toxic for patient use.

Dr Frederick Banting

In 1908, as detailed in his recent book, Insulin — the Crooked Timber, Hall also refers to the fact that a German researcher called Georg Zuelzer, MD, demonstrated in six patients that pancreatic extracts could reduce urinary levels of glucose and ketones, and that in one case, the treatment woke the patient from a coma. Zuelzer had purified the extract with alcohol but patients still experienced convulsions and coma; in fact, they were experiencing hypoglycemic shock, but Zuelzer had not identified it as such.

“He thought his preparation was full of impurities — and that’s the irony. He had in his hands an insulin prep that was so clean and so potent that it sent the test animals into hypoglycemic shock,” Hall points out.

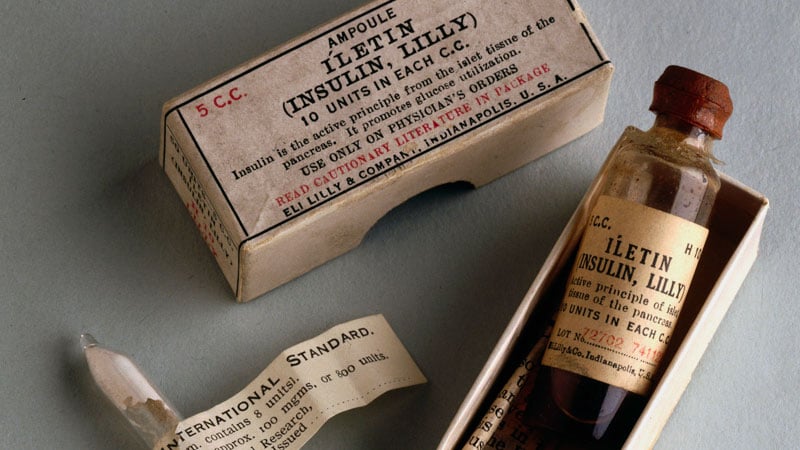

By 1921, two young researchers, Frederick Banting, MD, a practicing medical doctor in Toronto, together with a final year physiology student at the University of Toronto, Charles Best, MD, DSc, collaborated on the instruction of Best’s superior, John Macleod, MBChB, professor of physiology at the University of Toronto, to make pancreatic extracts, first from dogs and then from cattle.

Over the months prior to treating Thompson, working together in the laboratory, Banting and Best prepared the pancreatic extract from cattle and tested it on dogs with diabetes.

Then, in what amounted to a phase 1 trial of its day, with an “n of one,” a frail and close-to-death Thompson was given 15 cc of pancreatic extract at Toronto General Hospital in January 1922. His blood glucose level dropped by 25%, but unfortunately, his body still produced ketones, indicating the antidiabetic effect was limited. He also experienced an adverse reaction at the injection site with an accumulation of abscesses.

So despite successfully isolating the extract and administering it to Thompson, the product remained tainted with impurities.

At this point, colleague James Collip, MD, PhD, came to the rescue. He used his skills as a biochemist to purify the pancreatic extract enough to eliminate impurities.

When Thompson was treated 2 weeks later with the purified extract, he experienced a more positive outcome. Gone was the injection site reaction, gone were the high blood glucose levels, and Thompson “became brighter, more active, looked better, and said he felt stronger,” according to a publication describing the treatment.

Collip also determined that by over-purifying the product, the animals he experimented on could over-react and experience convulsions, coma, and death due to hypoglycemia from too much insulin.

Fighting Talk

Recalling an excerpt from Banting’s diary, Hall says that Banting had a mercurial temper and testified to his loss of patience with Collip when the chemist refused to share his formula of purification. His diary reads: “I grabbed him in one hand by the overcoat…and almost lifting him I sat him down hard on the chair…I remember telling him that it was a good job he was so much smaller — otherwise I would ‘knock hell out of him’.”

Dr John Macleod

According to Hall, in 1923, when Banting and Macleod were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine, Best resented being excluded, and despite Banting sharing half his prize money with Best, animosity prevailed.

At one point, before leaving on a plane for a wartime mission to the UK, Banting noted that if he didn’t make it back alive, “and they give my [professorial] chair to that son-of-a-bitch Best, I’ll never rest in my grave.” In a cruel twist of fate, Banting’s plane crashed and all aboard died.

The Nobel Prize had also been a source of rivalry between Banting and his boss, Macleod. In late 1921, while presenting the findings from animal models at the American Physiological Society conference, Banting’s nerves got the better of him and Macleod took over at the podium to finish the talk. Banting perceived this as his boss stealing the limelight.

Only a few months later, at the Association of American Physicians annual conference, Macleod played to an audience for a second time by making the first formal announcement of the discovery to the scientific community. Notably, Banting was absent.

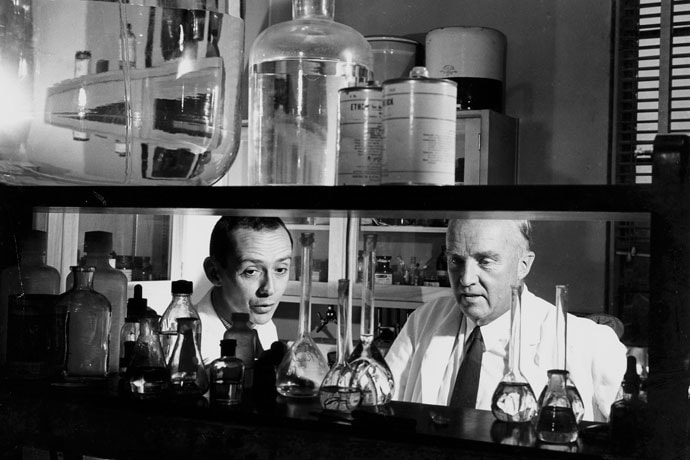

Dr Charles Best (right) with assistant (left) in the laboratory in 1960.

The Nobel Prize or a Poisoned Chalice?

Awarded annually for physics, chemistry, medicine/physiology, literature, peace, and economics, Nobel Prizes are usually considered the holy grail of achievement. In 1895, funds for the prizes were bequeathed by Alfred Nobel in his last will and testament, with each prize worth around $40,000 at the time (approximately $1,000,000 in today’s value).

Writing in 2001 in the journal Diabetes Voice, Professor Sir George Alberti, DPhil, BM BCh, former president of the UK Royal College of Physicians, summarized the burden that accompanies the Nobel Prize: “I personally believe that such prizes and awards do more harm than good and should be abolished. Many a scientist has gone to their grave feeling deeply aggrieved because they were not awarded a Nobel Prize.”

Such high stakes surround the prize that, in the case of insulin, the course of its discovery meant courtesies and truth were swept aside in hot pursuit of fame. After Macleod died in 1935 and Banting’s death in 1941, Best took the opportunity to try and revise history. There was the small obstacle of Collip, but Best managed to play down Collip’s contribution by focusing on the eureka moment as being the first insulin dose administered, despite the fact that a more complete recovery without side effects was only later achieved with Collip’s help.

Despite exclusion from the Nobel Prize, Best nevertheless became recognized as the “go-to-guy” for the discovery of insulin, says Hall. When Best spoke about the discovery of insulin at the New York Diabetes Association meeting in 1946, he was introduced as a speaker whose reputation was already so great that he did “not require much of an introduction.”

“And when a new research institute was opened in Toronto in 1953, it was named in his honor. The opening address, by Sir Henry Dale of the UK Medical Research Council, sang Best’s praises to the rafters, much to the disgruntlement of Best’s former colleague, James Collip, who was sitting in the audience,” Hall points out.

Both Hall and Stephens live with type 1 diabetes and have benefited from the efforts of Banting, Best, Collip, Zuelzer, and Macleod.

“The discovery of insulin was a miracle, it has allowed people to survive,” says Stephens. “Few medicines can reverse a death sentence like insulin can. It’s easy to forget how it was when insulin wasn’t there — and it wasn’t that long ago.”

Hall reflects that scientific progress and discovery are often portrayed as being the result of towering geniuses standing on each other’s shoulders.

“But I think that when German philosopher Immanuel Kant remarked that ‘Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing can ever be made,’ he offered us a much more accurate picture of how science works. And I think that there’s perhaps no more powerful example of this than the story of insulin,” he said.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article