In the brain, our perception arises from a complex interplay of neurons that are connected via synapses. But the number and strength of connections between certain types of neurons can vary. Researchers from the University Hospital Bonn (UKB), the University Medical Center Mainz and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich (LMU), together with a research team from the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt, as part of the Priority Program Computational Connectomics (SPP2041), have now discovered that the structure of the seemingly irregular neuronal connection strengths contains a hidden order. This is essential for the stability of the neuronal network. The study has now been published in the journal PNAS.

Ten years ago, connectomics, that is the creation of a map of the connections between the approximately 86 billion neurons in the brain, was declared a future milestone of science. This is because in complex neuronal networks, neurons are connected to each other by thousands of synapses. Here, the strength of the connections between individual neurons is important because it is crucial for learning and cognitive performance.

“However, each synapse is unique and its strength can vary over time. Even experiments that measured the same type of synapse in the same brain region yielded different values for synaptic strength. However, this experimentally observed variability makes it difficult to find general principles underlying the robust function of neuronal networks,” says Prof. Tatjana Tchumatchenko, research group leader at the Institute of Experimental Epileptology and Cognitive Research of the UKB and at the Institute of Physiological Chemistry of the University Medical Center Mainz, explaining the motivation to conduct the study.

Mathematics and laboratory combined purposefully

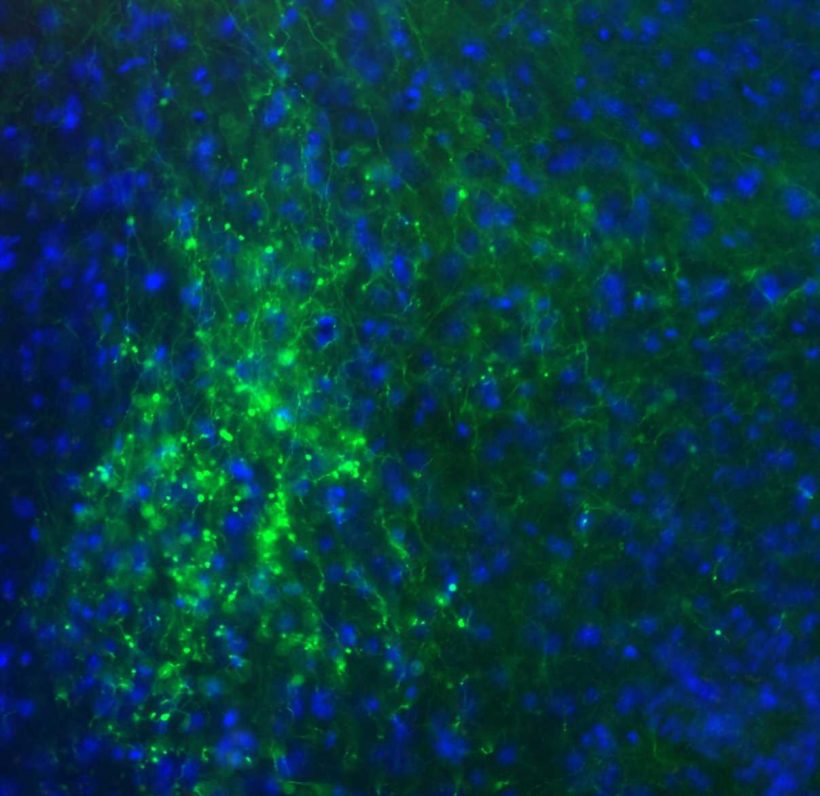

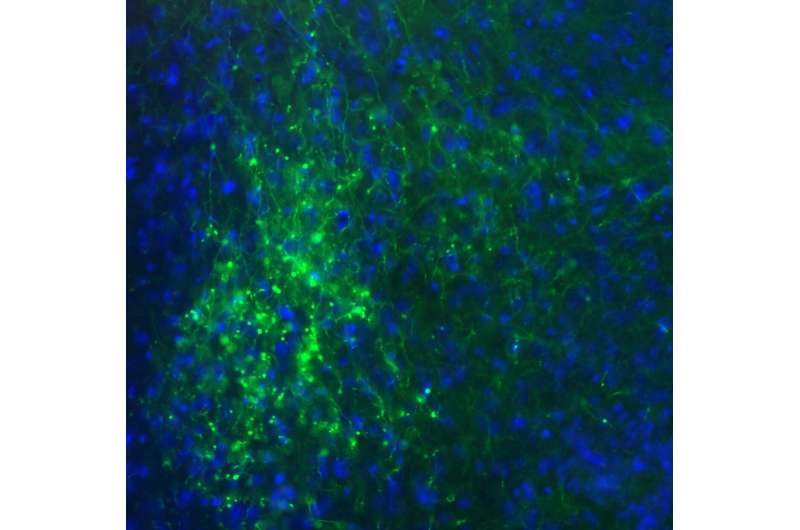

In the primary visual cortex (V1), the visual stimuli transmitted by the eye via the thalamus, a switching point for sensory impressions in the diencephalon, are first recorded. The researchers took a closer look at the connections between the neurons that are active during this process. To do this, the researchers measured experimentally the joint response of two classes of neurons to different visual stimuli in the mouse model. At the same time, they used mathematical models to predict the strength of synaptic connections. To explain their lab-recorded activities of such network connections in the primary visual cortex, they used the so-called “stabilized supralinear network” (SSN).

“It is one of the few nonlinear mathematical models that offers the unique possibility to compare theoretically simulated activity with actually observed activity,” says Prof. Laura Busse, research group leader at LMU Neurobiology. “We were able to show that combining SSN with experimental recordings of visual responses in the mouse thalamus and cortex allows us to determine different sets of connection strengths that lead to the recorded visual responses in the visual cortex.”

Sequence between the connection strengths is the key

The researchers found that there was an order behind the observed variability in synapse strength. For example, the connections from excitatory to inhibitory neurons were always the strongest, while the reverse connections in the visual cortex were weaker. This is because the absolute values of synaptic strengths varied in the modeling—as they had in the earlier experimental studies—but nevertheless always maintained a certain order. Thus, the relative ratios are crucial for the course and strength of the measured activity, rather than the absolute values.

“It is remarkable that analysis of earlier direct measurements of synaptic connections revealed the same order of synaptic strengths as our model prediction based on measured neuronal responses alone,” says Simon Renner, Ph.D., of LMU Neurobiology, whose experimental recordings of cortical and thalamic activity allowed characterization of the connections between cortical neurons.

Source: Read Full Article