For the first time, researchers have identified specific regions of the brain that are damaged by high blood pressure and may contribute to a decline in mental processes and the development of dementia.

High blood pressure is known to be involved in causing dementia and damage to brain function. The study, which is published in the European Heart Journal today, shows how this happens. It gathered information from a combination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brains, genetic analyses and observational data from thousands of patients to look at the effect of high blood pressure on cognitive function. The researchers then checked their findings in a separate, large group of patients in Italy.

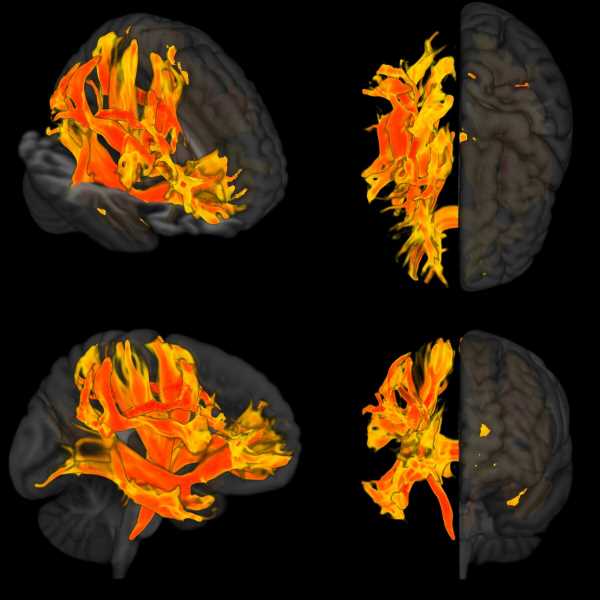

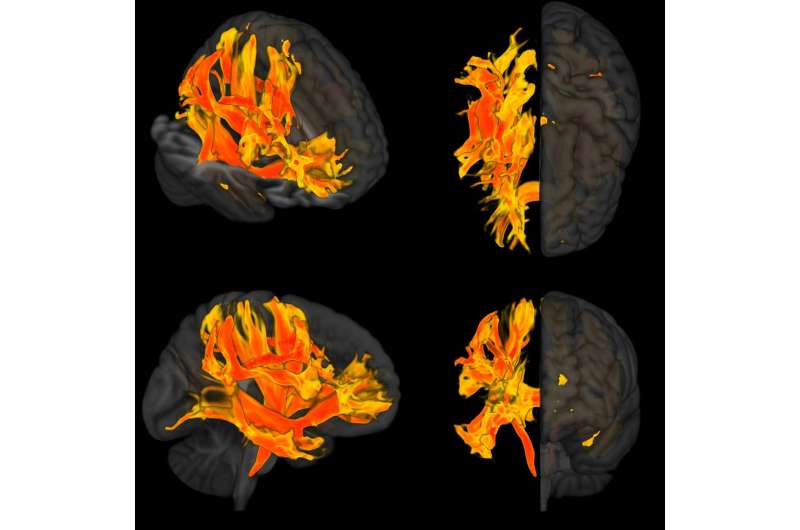

Tomasz Guzik, Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Edinburgh (UK) and Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow (Poland), who led the research, said, “By using this combination of imaging, genetic and observational approaches, we have identified specific parts of the brain that are affected by increases in blood pressure, including areas called the putamen and specific white matter regions. We thought these areas might be where high blood pressure affects cognitive function, such as memory loss, thinking skills and dementia. When we checked our findings by studying a group of patients in Italy who had high blood pressure, we found that the parts of the brain we had identified were indeed affected.

“We hope that our findings may help us to develop new ways to treat cognitive impairment in people with high blood pressure. Studying the genes and proteins in these brain structures could help us understand how high blood pressure affects the brain and causes cognitive problems. Moreover, by looking at these specific regions of the brain, we may be able to predict who will develop memory loss and dementia faster in the context of high blood pressure. This could help with precision medicine, so that we can target more intensive therapies to prevent the development of cognitive impairment in patients most at risk.”

High blood pressure is common and occurs in 30% of people worldwide, with an additional 30% showing the initial stages of the disease. Studies have shown that it affects how well the brain works and that it can cause long-term changes. However, until now it was not known exactly how high blood pressure damages the brain and which specific regions are affected.

Prof. Guzik and an international team of researchers used brain MRI imaging data from over 30,000 participants in the UK Biobank study, genetic information from genome-wide association studies (GWAS) from UK Biobank and two other international groups (COGENT and the International Consortium for Blood Pressure), and a technique called Mendelian randomization, to see if high blood pressure was actually the cause of changes to specific parts of the brain rather than just being associated with these changes.

“Mendelian randomization is a way of using genetic information to understand how one thing affects another,” said Prof. Guzik. “In particular, it tests if something is potentially causing a certain effect, or if the effect is just a coincidence. It works by using a person’s genetic information to see if there is a relationship between genes predisposing to higher blood pressure and outcomes. If there is a relationship, then it is more likely that the high blood pressure is causing the outcome. This is because genes are randomly passed down from parents, so they are not influenced by other factors that could confuse the results. In our study, if a gene that causes high blood pressure is also linked to certain brain structures and their function, then it suggests that high blood pressure might really be causing brain dysfunction at that location, leading to problems with memory, thinking and dementia.”

The researchers found changes to nine parts of the brain were related to higher blood pressure and worse cognitive function. These included the putamen, which is a round structure in the base of the front of the brain, responsible for regulating movement and influencing various types of learning. Other areas affected were the anterior thalamic radiation, anterior corona radiata and anterior limb of the internal capsule, which are regions of white matter that connect and enable signaling between different parts of the brain. The anterior thalamic radiation is involved in executive functions, such as the planning of simple and complex daily tasks, while the other two regions are involved in decision-making and the management of emotions.

The changes to these areas included decreases in brain volume and the amount of surface area on the brain cortex, changes to connections between different parts of the brain, and changes in measures of brain activity.

The first author of the study, Associate Professor Mateusz Siedlinski, also a researcher at Jagiellonian University Medical College, said, “Our study has, for the first time, identified specific places in the brain that are potentially causally associated with high blood pressure and cognitive impairment. This was uniquely possible thanks to the availability of data from UK Biobank, including MRI brain images, and thanks to previous research identifying genetic variants that affect the structure and function of over 3000 areas of the brain.”

Co-author of the study Professor Joanna Wardlaw, Head of Neuroimaging Sciences at the University of Edinburgh, said, “It has been known for a long time that high blood pressure is a risk factor for cognitive decline, but how high blood pressure damages the brain was not clear. This study shows that specific brain regions are at particularly high risk of blood pressure damage, which may help to identify people at risk of cognitive decline in the earliest stages, and potentially to target therapies more effectively in future.”

Limitations of the study include that participants in the UK Biobank study are mainly white and middle-aged, so it might not be possible to extrapolate the findings to older people.

An accompanying editorial is written by Dr. Ernesto Schiffrin, from Sir Mortimer B. Davis-Jewish General Hospital and McGill University, Montreal, (Canada), and Dr. James Engert, from the McGill University Health Centre Research Institute, Montreal. They observe that “further mechanistic studies of the effects of BP [blood pressure] on cognitive function are required to determine precise causal pathways and relevant brain regions.”

They also highlight one of the study’s findings about systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP): “Perhaps one of the more interesting results in this study is the possible distinct causal effects of SBP vs. DBP. The authors observed some overlapping results for SBP and DBP on cognitive function when analyzed in isolation. However, when each parameter is analyzed after adjusting for the other, or in multivariable models, intriguing findings begin to emerge. DBP alone does not predict a decline in cognitive function, but in fact, is protective when adjusted for SBP. This result was true both observationally and when using Mendelian randomization,” they write, and continue by discussing the possible reasons for this.

More information:

Tomasz J Guzik et al, Genetic analyses identify brain structures related to cognitive impairment associated with elevated blood pressure, European Heart Journal (2023). DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad101

Ernesto L. Schiffrin et al, Hypertension, brain imaging phenotypes and cognitive impairment: lessons from Mendelian randomisation, European Heart Journal (2023). DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad187

Journal information:

European Heart Journal

Source: Read Full Article