A multidisciplinary study led by Vanja Nagy (LBI-RUD/CeMM/Medical University of Vienna) and Josef Penninger (UBC/IMBA) characterized a novel gene, known as FIBCD1, to be likely causative of a new and rare neurodevelopmental disorder. Using data from two young patients with neurological symptoms, the researchers from both groups found evidence of a novel function for the FIBCD1 gene in the brain, and a potentially pivotal role in diseases such as autism, ADHD, schizophrenia, and neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s. The study makes an important contribution to the understanding of the extracellular matrix in the brain and its associated neurological diseases.

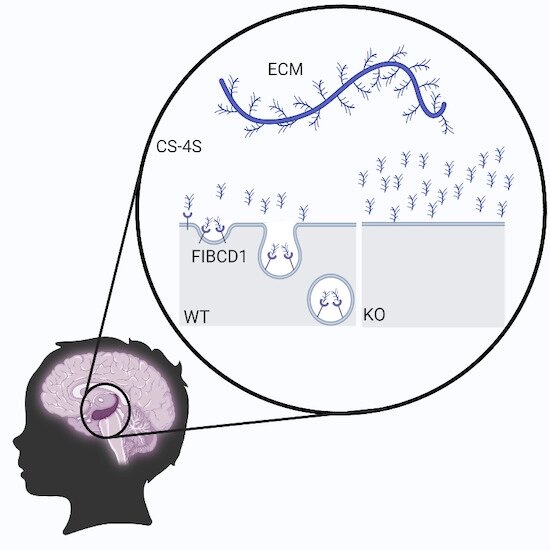

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is the tissue in the brain that surrounds cells in a meshwork-like manner to support and instruct brain function in that respective region. The ECM provides stability to brain cells to enable proper function, including long-term memory storage, and makes up around a fifth of the brain volume. Until now, few cellular receptors for ECM signaling have been identified, but no association with a congenital neurological disease was made. For the first time, researchers from two groups—Vanja Nagy’s group from the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Rare and Undiagnosed Diseases (LBI-RUD), the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW), and Josef Penninger’s group from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW)—have characterized FIBCD1, to be a receptor of the ECM “sugar” components and linked it to a rare genetic neurological disease. “Until now, we were only aware of FIBCD1 in an immunological context, and it had never been studied in the brain or in connection with our central nervous system function. FIBCD1 is highly expressed in the brain, and it binds to sugar-based molecules. Since the brain ECM consists predominantly of sugar, we theorized that the receptor must contribute to brain function through ECM binding and/or signaling,” explains Vanja Nagy, the principal investigator of the study.

Mutated FIBCD1 receptors in patients with neurological disorders

First authors Christopher Fell (LBI-RUD/CeMM) and Astrid Hagelkruys (IMBA) used knockdown fly and knockout mouse models, as well as a series of in silico and in vitro experiments, to demonstrate that FIBCD1 is indeed a receptor for ECM components in the brain. Their work confirmed that the absence of FIBCD1 can lead to nervous system disorders that affect behavior and cellular dysfunction in animal models. “This allowed us to conclude that deleterious variants in FIBCD1 could also cause neurological disorders in humans,” Fell and Hagelkruys explained. This conclusion is also supported by the data from two young patients with neurodevelopmental symptoms, one from the United States and one from China, for whom no diagnosis could be made prior to characterization of FIBCD1’s expression and function in brain neurons. Both patients suffer from a variety of devastating symptoms primarily affecting their central nervous system, including autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), delayed developmental milestones, language impairments, and structural brain anomalies. In both patients, a mutation or variant in FIBCD1 was identified, thereby establishing an important diagnostic milestone.

The link between FIBCD1 and the brain raises many new questions

“We were already able to see in the animal models that the inactivation of FIBCD1 leads to massive neuronal functional perturbance,” Vanja Nagy explains. “In the affected patients, we determined that in both cases, the FIBCD1 variants identified are functionless—the binding to sugars does not work. We have therefore determined that this might be the possible underlining pathological mechanism in the disease of the patients.” Despite this fact, the symptoms of the two patients were remarkably different: while one of the patients had structural abnormalities in the brain, the other patient did not. “To be able to make a more concrete determination about the function of FIBCD1 in the human central nervous system, and what it can trigger if mutated, a much larger study cohort is needed,” Nagy added.

Intensive collaboration for research into rare diseases

Source: Read Full Article